ANTIGUA | Below the Surface: The Rise of Jamale Pringle

How a man from Swetes is restoring Antigua’s authentic political tradition—and leaving the credentialed elite scrambling

A WiredJa Feature

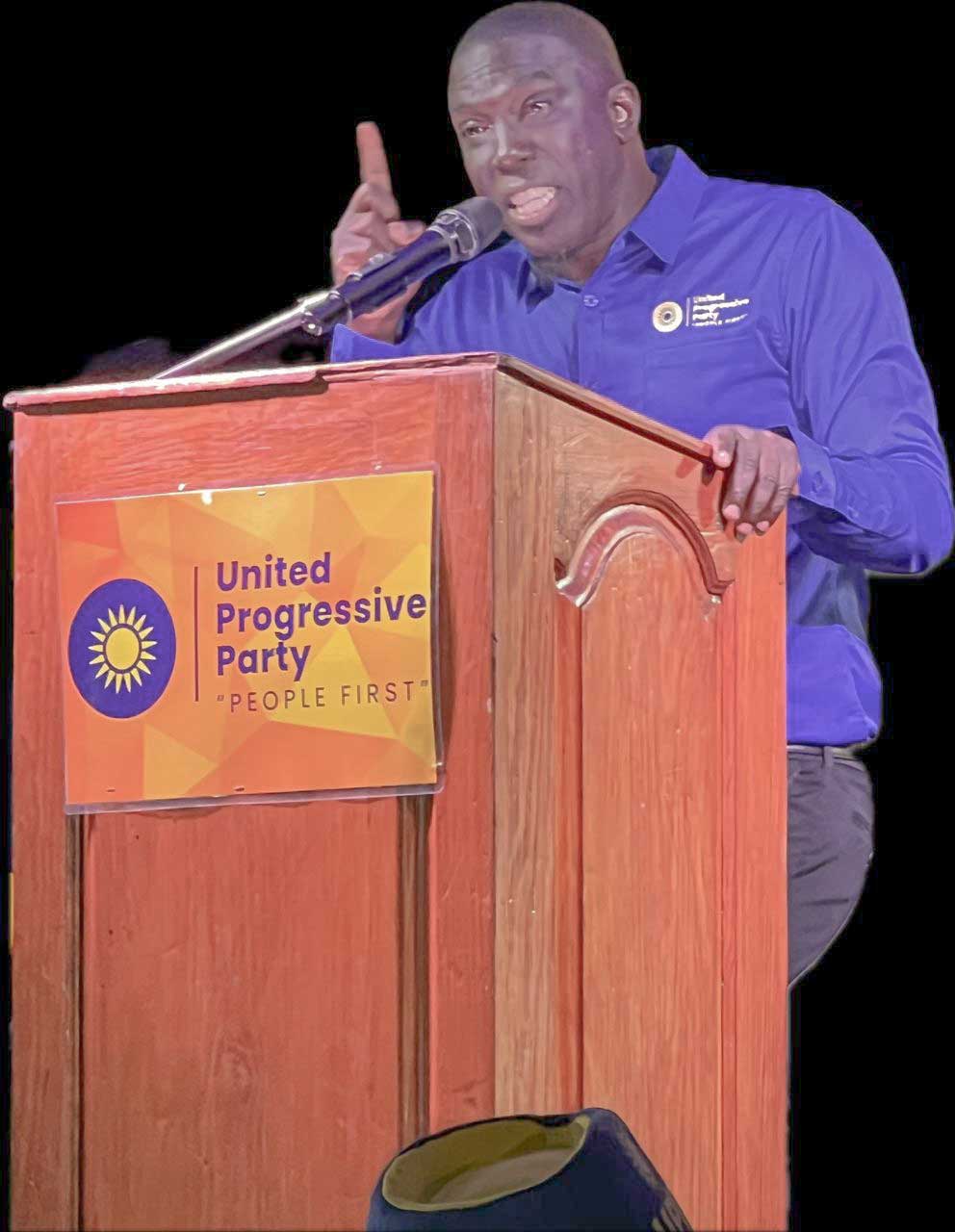

There is a story they tell in Antigua about Jamale Pringle—one that says more about the man than any campaign speech or parliamentary debate ever could. It involves a dead dog, a claustrophobic crawlspace, and the kind of work that men with university degrees and polished surnames would never dream of doing themselves.

In his early years as a businessman, Pringle held a contract with National Solid Waste for cleaning public market areas and removing deceased animals. When an elderly resident called about a dead creature beneath her house—a task that fell outside his contractual obligations—Pringle didn’t delegate.

He crawled into a foot-high space himself, grappling with malodorous remains while his brother, overcome by the stench, lost his lunch on the spot.

This is the man who now leads Antigua and Barbuda’s opposition. This is the man the intellectual elites thought they could dismiss.

This is the man who has run rings around those who believed that academic letters and professional pedigrees were the prerequisites for political leadership.

They were wrong. And now, as the prospect of snap elections looms and polls suggest Pringle could actually win, those who once scoffed find themselves in an uncomfortable position: watching from the sidelines as the man they underestimated reshapes the political landscape they thought belonged to them.

The Tradition They Forgot

V.C. Bird, the Father of the Nation and first Prime Minister, built a country without the benefit of academic credentials. Baldwin Spencer, who led the UPP to its historic 2004 victory, possessed no letters after his name.

These were men of the earth—leaders forged in trade unions and community halls, in the struggle for workers’ rights and national independence. They did not emerge from law faculties or professional sinecures. They emerged from the people, and the people recognised them as their own.

The credentialed politicians—those who came later with their university degrees and professional qualifications—are actually the anomaly in Antiguan political history, not the norm.

When critics question whether Pringle has the “credentials” for leadership, they reveal not their sophistication but their ignorance of the very tradition they claim to uphold.

Jamale Pringle does not represent a break from Antigua’s political heritage. He represents its restoration.

Roots in the Black Earth

He is the product of historically enslaved African families who built Antigua with their hands and their sweat—families who survived the brutality of colonialism and emerged, generation after generation, to claim their place on soil that was never meant to be theirs.

Rising from the village of Swetes, Pringle embodies something increasingly rare in Caribbean politics: authenticity uncorrupted by colonial pretension.

In a region where political elites often measure their worth by proximity to European traditions and institutions, Pringle stands as a man shaped by the Caribbean itself, unbowed by the inherited hierarchies that continue to haunt post-colonial societies.

This heritage is not incidental to his politics. It is foundational. When Pringle speaks of the struggles facing ordinary Antiguans—the crushing electricity bills, the water that “flows with tears of despair,” the healthcare system “on life support”—he speaks not as an observer looking down from professional heights, but as someone who emerged from the very communities he seeks to serve.

The Businessman Before the Politician

Before Pringle ever set foot in Parliament, he built something from nothing. His business acumen was forged not in lecture halls or boardrooms, but in the unglamorous trenches of entrepreneurship where success is measured by results, not credentials.

The “Dead Dog” story, as it has come to be known, serves as a powerful metaphor for Pringle’s approach to leadership. In a political climate where many leaders shy away from the messy, unappealing aspects of public service, Pringle demonstrated a willingness to roll up his sleeves and tackle the most unpalatable tasks head-on.

No task was beneath him. No work was too dirty. This is the mentality that built his business—and it is the mentality that defines his politics.

As one famous Caribbean politician—a prominent lawyer himself—once cautioned: “Being a lawyer or an academic cannot make you a good politician.” The credentialed class has always struggled with this truth.

They assume that professional achievement translates automatically into political effectiveness, that university degrees confer wisdom in the art of governance. Pringle’s rise—like the rise of Walter, Bird, and Spencer before him—is a rebuke to that assumption.

The Lone Parliamentarian

In the 2018 general elections, while the established leaders of the United Progressive Party fell to defeat, Jamale Pringle stood alone. He was the only UPP candidate to win his seat—All Saints East & St. Luke—while those who considered themselves the party’s natural leadership nursed the wounds of electoral rejection.

For five years, Pringle faced a Parliament more inclined to jeer than to cheer. He endured the isolation of opposition without the comfort of colleagues beside him. Where others might have wilted under such pressure, Pringle’s resolve only hardened.

The crucible of those years forged a political operator of remarkable resilience—a man who learned the craft of opposition not in theory, but in the brutal daily practice of standing alone against a hostile chamber.

Critics who once mistook Pringle’s measured speech for a lack of acumen came to recognize the depth of thought behind his words. As one former opponent aptly noted, judging Pringle on a single aspect of his persona is akin to assessing a centipede’s performance based on the movement of a single leg.

Like an iceberg, where the majority of its mass lurks unseen beneath the waves, Pringle’s public persona is merely the tip of something far more substantial.

The Convention Coup

They had the credentials. They had the connections. They had, they believed, the inevitable momentum of professional superiority. The rank and file had other plans.

In a stunning rejection of establishment assumptions, the UPP’s grassroots membership chose Jamale Pringle as their leader. It was a democratic earthquake that left the credentialed elite reeling.

The man from Swetes—the businessman who crawled under houses, the lone parliamentarian who survived five years of isolation—had outmaneuvered those who thought academic letters entitled them to leadership.

In choosing Pringle, the UPP’s membership did something profound: they returned their party to the authentic tradition of Antiguan political leadership. They rejected the credentialed interlopers in favour of a man cut from the same cloth as the founders.

The bitter pill has yet to be swallowed. And therein lies the ongoing drama that threatens to consume the UPP from within.

The Sulking Caucus

Since Pringle’s elevation to leadership, a curious pattern has emerged among certain MPs elected under the UPP banner. Conspicuous absences from party functions. Tepid support for the party’s direction. Carefully calibrated middle-of-the-road stances that suggest divided loyalties. Frequent overseas sojourns while the party fights for its political life at home.

They behave, in short, like children who have lost their favourite toy—pouting in the corner, grumbling about the unfairness of it all, waiting for the adults to recognise their mistake and restore the natural order of things.

Some have been conspicuously absent from public meetings. Others have distanced themselves from the party’s platform even as they sit in Parliament under its name.

The very representatives elected on the strength of the UPP’s message now seem reluctant to fully embrace the party’s direction under Pringle’s leadership.

Political observers point to these internal fissures as evidence of a deliberate strategy: embarrass Pringle, undermine his authority, wait for him to fail—and then swoop in to reclaim what they believe was always rightfully theirs.

But there is a fear driving this resentment that the old guard dares not speak aloud.

The Fear That Dare Not Speak Its Name

What if Pringle wins?

With snap elections a persistent possibility and polls showing Pringle increasingly competitive against Prime Minister Gaston Browne, the nightmare scenario for the sulking caucus is coming into focus. A Pringle victory would not merely validate his leadership—it would permanently close the door on those who expected to return to power on their own terms.

They want a do-over. They believe they deserve one. Having been kicked out by the rank and file in Pringle’s favour, they cannot accept that the people have spoken.

They seek every opportunity to denigrate the man who beat them at their own game—not through superior credentials, but through superior connection to the grassroots, superior resilience under fire, and superior understanding of what ordinary Antiguans actually want from their leaders.

The irony is exquisite. Those who claimed Pringle lacked the sophistication for leadership now find themselves outmanoeuvred at every turn. Those who questioned his political acumen watch as he methodically builds support while they retreat into irrelevance.

Those who thought their academic credentials entitled them to power discover that the people prefer authenticity to pedigree—just as they always have in Antigua.

The Leader in Action

In his blistering critique of the government’s 2025 Budget, Pringle exposed what he called “star-studded political theatre” that offered “little style and less substance.” His dissection of the administration’s failures—on water, on electricity, on healthcare, on food security—demonstrated the kind of forensic policy analysis that his detractors claimed he was incapable of delivering.

He walks through St. John’s Market engaging with vendors and farmers. He maintains direct contact with citizens in ways that politicians of the credentialed class often find beneath their dignity. He speaks of food security not as an abstract policy goal but as “the cornerstone of our national resilience.”

When political attacks come—and they come relentlessly—Pringle does not cower. Recent attempts to question him over vandalism allegations were met with characteristic defiance: “They cannot muzzle me.” The UPP has framed such actions as political persecution, and whether or not one agrees with that characterisation, the pattern is clear: Pringle refuses to be intimidated.

The Iceberg Rises

In 1998, the Antiguan calypso artist Mystic Prowler released a song called “Below the Surface.” Its central metaphor—that what you see above the water reveals nothing about the true mass beneath—applies perfectly to Jamale Pringle.

For too long, Pringle’s critics assessed him on surfaces: his speaking style, his lack of formal legal training, his emergence from business rather than the professions that traditionally supply Caribbean political leadership. They saw the tip of the iceberg and assumed there was nothing more.

They were catastrophically wrong.

Beneath that surface lies a bedrock of humility forged through unglamorous work. Beneath it lies the resilience of a man who survived five years as a lone parliamentarian. Beneath it lies the strategic mind that outmanoeuvred the credentialed elite at their own convention.

Beneath it lies something the old guard has always lacked: an authentic connection to the people of Antigua and Barbuda.

And beneath it all lies something his critics never understood: Jamale Pringle is not an aberration in Antiguan political history. He is its continuation. He stands in the lineage of Walter, Bird, and Spencer—men who led not because of credentials conferred by foreign institutions, but because the people recognised in them something genuine, something rooted, something real.

The sulking caucus can continue to pout. The old guard can continue to dream of do-overs. But the iceberg has risen, and those who mistook the tip for the whole are about to discover the true depth of what lies below.

— 30 —