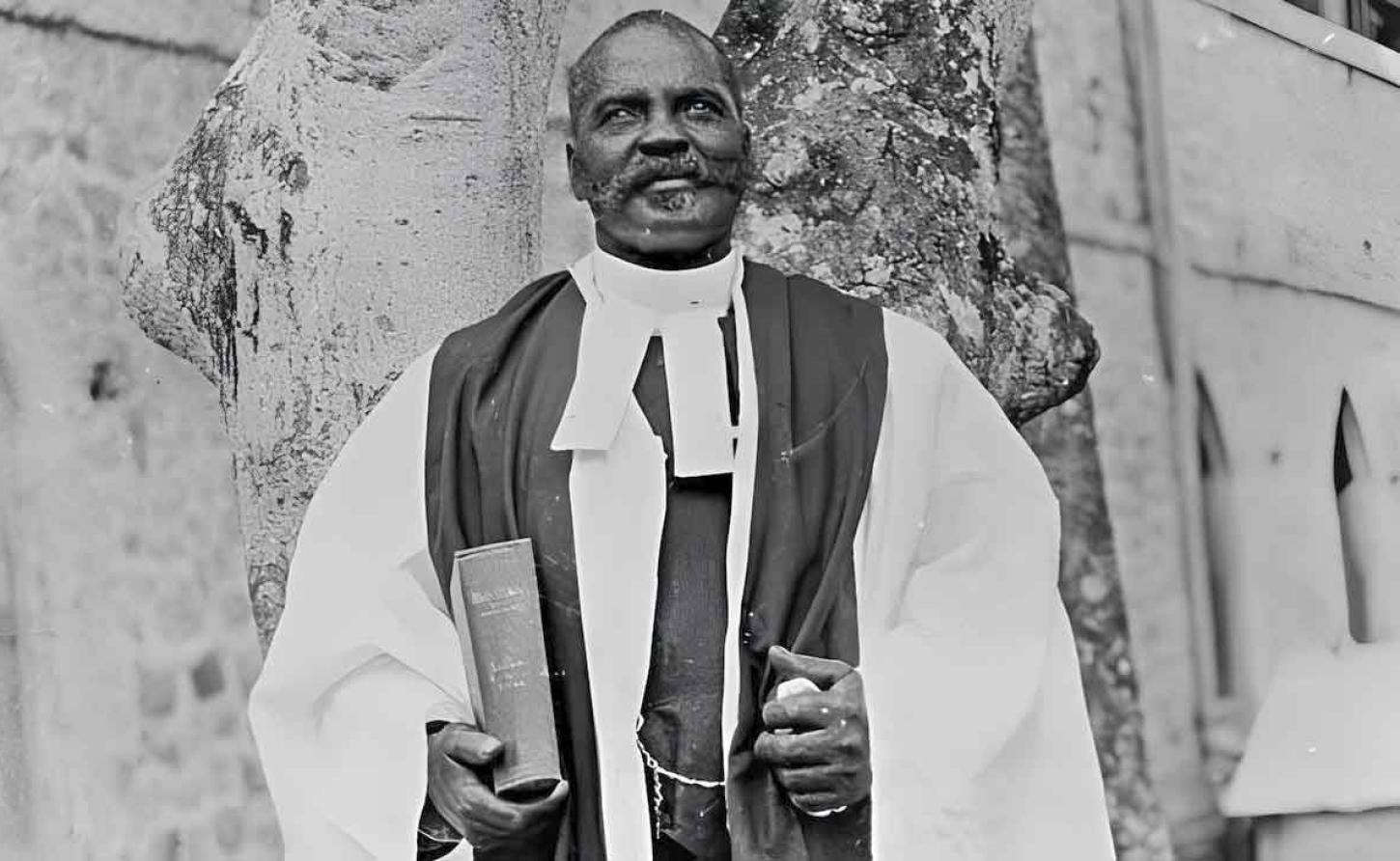

JAMAICA | How Colonial Jamaica Silenced Alexander Bedward by Referring to him as “A Mad Man”

By O. Dave Allen

When colonial authorities arrested Alexander Bedward in 1921 and declared him insane, they weren't diagnosing mental illness—they were executing a calculated strategy to destroy Jamaica's most powerful Black religious leader.

With 30,000 followers across 125 congregations spanning Jamaica, Cuba, and Central America, Bedward commanded a mass movement that rivaled any political organization in colonial Jamaica. His crime wasn't madness. It was demanding Black liberation from white supremacy.

"There is a white wall and a black wall, and the white wall has been closing around the black wall," Bedward preached in his most famous sermon. "But now the black wall has become bigger than the white wall and they must knock the white wall down." For these words, colonial authorities branded him seditious. When that failed to silence him, they called him insane.

The pattern was deliberate. In 1895, after his "white wall, black wall" sermon, Bedward was tried for sedition. The jury deliberated just forty minutes before returning an extraordinary verdict: not guilty by reason of insanity.

He was committed to the Kingston Lunatic Asylum—neither acquitted nor imprisoned, but discredited. His lawyer secured his release within a month through habeas corpus, arguing the absurdity: "You cannot try a man for sedition and sentence him to an asylum."

But Bedward's movement only grew stronger. By 1920, he led a hierarchical organization with twenty-four elders, seventy-two evangelists, and a network of camps throughout Jamaica.

In 1921, when Bedward marched to Kingston with 700 followers, Governor Sir Leslie Probyn deployed two platoons of the Sussex Regiment armed with rifles. Authorities arrested 685 marchers, charging them under the Vagrancy Act despite most being employed workers.

Over 200 followers were tried, convicted, and sentenced within four hours, without legal representation. Bedward himself was released from vagrancy charges, then immediately re-arrested and declared insane.

He spent the final nine years of his life confined in the Kingston Lunatic Asylum, where he died on November 8, 1930.

Colonial psychiatry wasn't medicine—it was social control. As University of the West Indies Professor Frederick W. Hickling argues, from the perspective of African descendants, "the institutionalization of the mentally ill is merely an extension of slavery."

Colonial physicians were "all Britons doing Colonial Service, carrying out the 'civilizing mission' of the British Empire." Following the Morant Bay Rebellion, the colonial administration grew suspicious of Revivalist communities as "incubators of a backwards Africanized culture that fostered insurrection."

The popular story that Bedward attempted to physically fly to heaven—used for generations to characterize him as delusional—appears to be largely posthumous fabrication. The Jamaica Observer notes that "there is no record of any attempt by Bedward or his followers to fly."

Critically, "if ever he attempted to fly, the colonial authorities and The Gleaner, which had a keen eye on him, would have certainly used it as further ammunition to discredit and ridicule him. They did not." The colonial authorities arrested and institutionalized Bedward for his march—not for any "flying" incident.

Yet Bedward's influence outlasted his imprisonment. Robert Hinds, one of Rastafari's founders and Leonard Howell's second-in-command, was a Bedwardite arrested during the 1921 march.

Scholars explicitly identify Bedward as "one of the forerunners of Marcus Garvey and his brand of pan-Africanism." As scholar Dave St. Aubyn Gosse concludes, Bedward "affirmed Africa, its culture and traditions, laid the foundation for later black nationalist movements such as Garveyism and Rastafari."

The pattern repeated across Jamaican history: Paul Bogle hanged after Morant Bay, Marcus Garvey imprisoned and deported, Leonard Howell sent to Bellevue Asylum. Religious leaders advocating Black dignity; colonial response through sedition charges, imprisonment, or psychiatric institutionalization; subsequent historical distortion.

As scholar Anthony Bogues observed, Bedward's only "insanity" was his attempt to "break and reorder the epistemological rationalities of colonial conquest." They called him mad because they couldn't allow him to be right.

—30—

You can respond to O. Dave Allen at