JAMAICA | Miss Pat: The Quiet Architect of Reggae’s Global Conquest: VP Records

How Patricia Chin and VP Records built a bridge from Kingston’s streets to the world’s speakers

By WiredJa

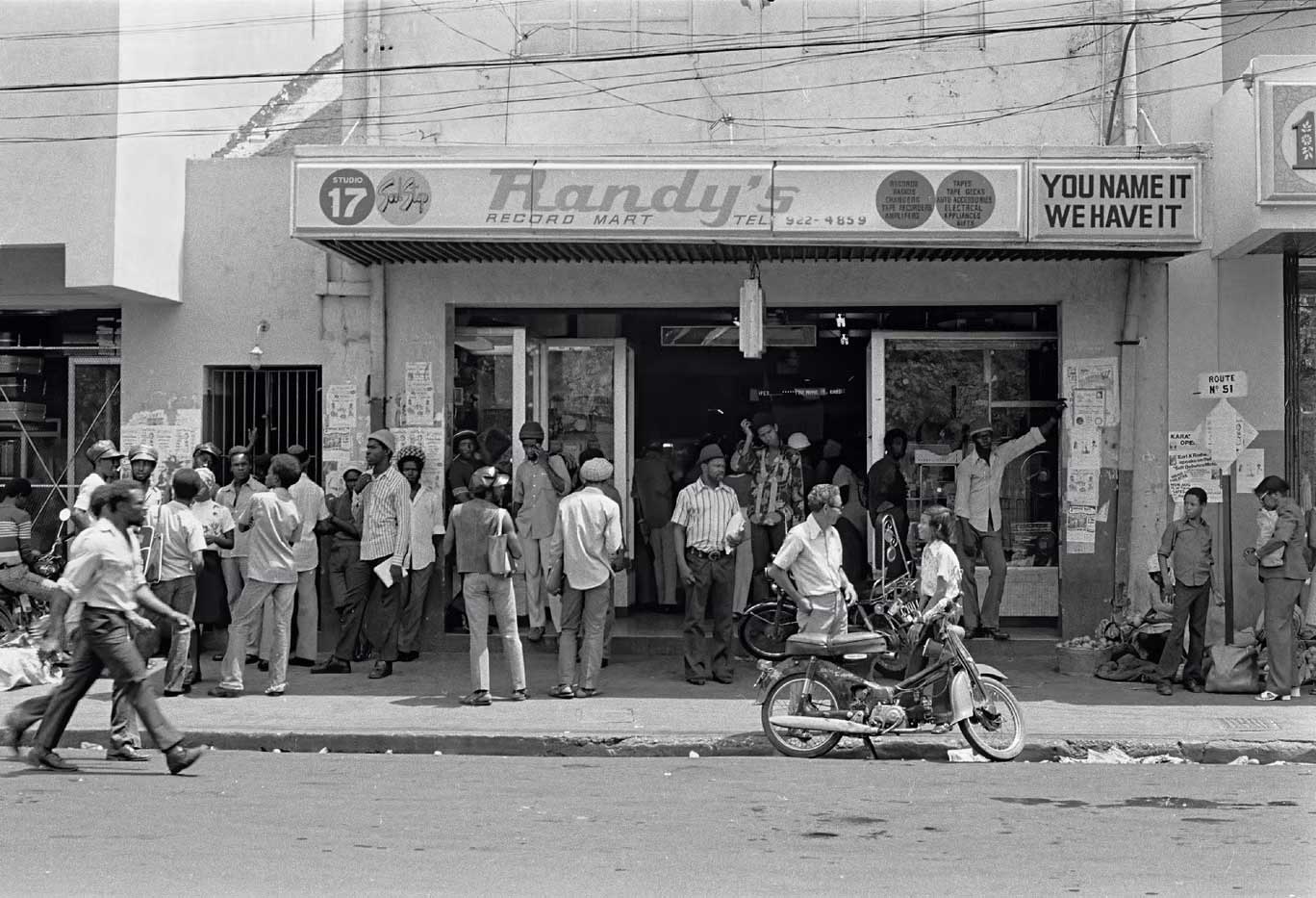

KINGSTON, Jamaica, February 4, 2026 - The year was 1979, and Patricia Chin was standing in her record shop at 17 North Parade, Kingston, watching something extraordinary unfold through the storefront window.

On the streets below, bodies moved to a new rhythm—faster, rawer, more urgent than the roots reggae that had dominated the decade. Dancers invented moves in real time, responding to the sparse, propulsive beats emanating from nearby sound systems.

“Oh my god, it was so exciting, and so different,” Miss Pat recalls of her first encounters with dancehall. “We could see all the people dancing on the street. You could feel the energy of the people, you know? It was a new beat and new times.”

What Miss Pat witnessed from that North Parade vantage point was nothing less than a musical revolution—one she would help export to every corner of the globe.

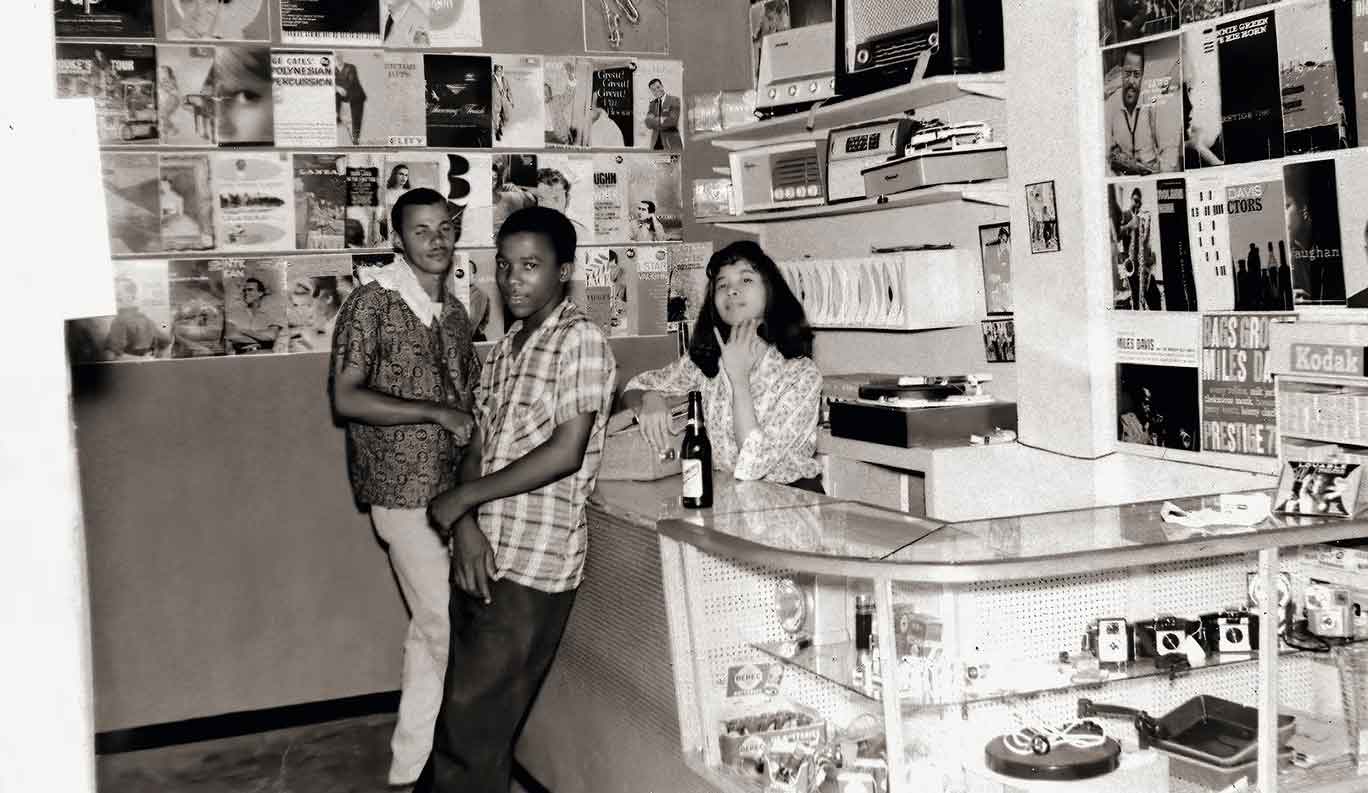

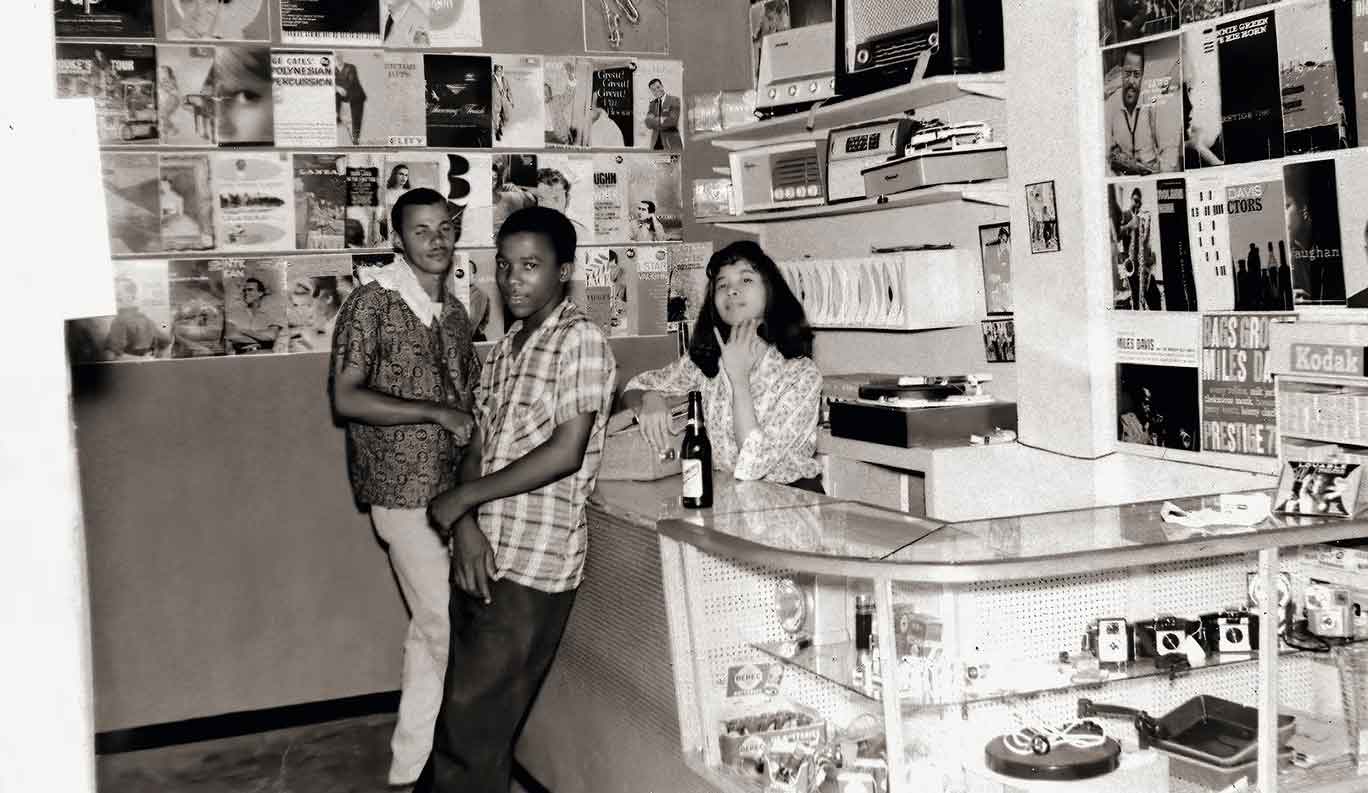

Pat and Randy Chin at Randy's Records in Jamaica 1960sFrom Ice Cream Parlour to Cultural Institution

Pat and Randy Chin at Randy's Records in Jamaica 1960sFrom Ice Cream Parlour to Cultural Institution

The VP Records story begins not in a boardroom or recording studio, but in an ice cream parlour at 36 East Street, Kingston. It was there that Patricia and her husband Vincent “Randy” Chin opened a modest secondhand record shop, selling imported American R&B and jazz to Kingston’s music-hungry public.

The Chins possessed something invaluable: an ear perpetually tuned to the streets. As Jamaica’s musical landscape evolved, so did their business. Randy’s—as the shop became known—relocated to the now-legendary North Parade address, transforming from retail outlet to recording hub. The transition was organic, almost inevitable. When you spend your days surrounded by people hungry for the newest sounds, you learn to anticipate what they’ll want next.

Miss Pat’s background perhaps predisposed her to bridge-building. Born in Kingston to a Chinese mother and Indian father, she embodied Jamaica’s multicultural tapestry long before “diversity” became corporate vocabulary. Her identity was forged in the island’s great tradition of cultural synthesis—the same tradition that produced reggae itself.

Reading the Streets: VP’s A&R Philosophy

The genius of VP Records—and of Miss Pat specifically—lay in understanding that hit-making isn’t about imposing taste but about listening. When dancehall began displacing roots reggae in the late 1970s, many established players dismissed it as a passing fad, too raw and “slack” for international consumption.

The Chins saw differently.

“You know at VP and Randy’s, we always had our ear to the street,” Miss Pat explains. “When people used to come into the store and ask me for all these dancehall records, that’s why I knew it was going to last.”

What distinguished VP from competitors was its understanding that dancehall wasn’t merely music—it was a complete cultural package. “For each genre of music, there’s a different way of dancing with the music,” Miss Pat observes. The label promoted not just records but an entire aesthetic, recognizing that the relationship between sound and movement was inseparable from dancehall’s appeal.

The Diaspora Strategy: Jamaica, Queens

In 1977, the Chins made a pivotal decision: relocation to New York. After a brief Brooklyn sojourn, they settled in Jamaica, Queens—the coincidence of the name almost too perfect to be accidental.

In those early years, it was Vincent who did much of the leg work—building relationships, establishing distribution networks, and laying the commercial foundations that would sustain the business.

But as the operation grew, Randy eventually shifted his focus to other aspects of the enterprise, leaving the day-to-day operations increasingly in Miss Pat’s capable hands. It was a transition that would prove pivotal, as her business acumen and deep understanding of the music would guide VP through decades of industry upheaval.

The move was strategically brilliant. New York’s Caribbean diaspora numbered in the hundreds of thousands, a ready-made market hungry for sounds from home. But more importantly, the city offered infrastructure: distribution networks, recording facilities, and proximity to the American music industry’s power centres.

From Queens, VP could service both the nostalgic diaspora market and pursue crossover ambitions. The label became a two-way conduit—importing authentic Jamaican music to American shores while channeling American resources and reach back to Caribbean artists.

The Radio Pipeline: Barnes, Williams, Bailey, and the Sound of Home

When Miss Pat arrived in New York in the late 1970s, Caribbean music had virtually no presence on American radio.

West Indian immigrants hungry for sounds from home had few options beyond house parties and local bars. Into this void stepped a cadre of broadcasters who would transform the landscape.

Jeff Barnes and Carl Anthony at WWRL in Queens, and Kenardo Williams at WLIB 1190 AM, emerged as the first major forces in Caribbean radio during the 1970s.

Williams, who also worked at WBLS, rose to become Program Director at WLIB—a position of significant influence that allowed him to shape the station’s Caribbean programming and open doors for the music to reach wider audiences.

Then there was Ray Dinham, who went by the name "Ray-D" on WVOX and WRTN in New Rochelle, New York, as part of the pioneering Caribbean radio presence in the diaspora.

These pioneers laid the groundwork at a time when mainstream American radio wanted nothing to do with reggae or its Caribbean cousins.

Gil Bailey, who would eventually earn the title “Godfather of Reggae Radio,” took a different path.

Having launched his broadcasting career in 1969 on WHBI, Bailey’s rise was gradual—built over years of persistence and dedication buying broadcast time slots on the station and selling commercials to pay for the broadcast.

He slowly developed into a force to be reckoned with, eventually co-hosting marathon nine-hour Saturday programmes with his wife Pat on stations including WNWK and WPAT.

His broadcasts became appointment listening for Caribbean immigrants across New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Miss Pat recognized these broadcasters as kindred spirits—forward-thinking champions of a culture the American mainstream ignored.

“I was introduced to Gil Bailey when I came to New York 40 years ago,” she later recalled, “and he was one of the only ones who was forward-thinking about the music and culture.”

VP Records, with its direct pipeline to Jamaican producers and its encyclopaedic inventory, became the destination of choice.

The DJs needed fresh music to maintain their audiences; VP needed exposure to move product. Together, they built the infrastructure that made Caribbean music accessible to an entire generation of immigrants longing for home.

This ecosystem—radio personalities, record distributors, and an audience desperate for cultural connection—represented something larger than commerce. It was community-building through sound, a way of maintaining identity across oceans.

The Globalisation of Jamaican Sound

By the time VP Records celebrated its 40th anniversary with the sprawling compilation “Down In Jamaica,” the label had achieved something remarkable: it had become the world’s largest independent reggae distributor without sacrificing its roots credibility.

The achievement deserves contextualizing. The global music industry is littered with the corpses of independent labels absorbed by majors or bankrupted by shifting technologies.

VP not only survived but thrived, navigating the transition from vinyl to CD to digital streaming while maintaining family ownership.

More significantly, VP helped establish the template by which Jamaican music would influence global pop.

Today, when Drake adopts dancehall flows or Rihanna rides a Caribbean-inflected riddim, they’re building on foundations that labels like VP laid.

The “tropical house” moment of the mid-2010s, the dancehall revival in contemporary hip-hop—none of this happens without decades of groundwork by distributors who kept the music circulating and evolving.

Miss Pat understood something that many music industry observers missed: dancehall’s appeal wasn’t despite its roughness but because of it. “It was music that inspired people to get up and move,” she reflects. “And it still is. At parties, whenever you hear dancehall music come on, you see people start to rock and move and feel good.”

Legacy: More Than a Businesswoman

Now in her 80s, Miss Pat remains deeply connected to the music and culture she helped globalize. Her story is one of entrepreneurial vision, certainly—but reducing it to business success misses the larger significance.

DJ Kool Herc, widely credited as the founder of hip-hop, once observed: “What Berry Gordy was to Motown Records, Patricia Chin is to the reggae industry.” The comparison is apt. Like Gordy, Miss Pat didn’t merely release records—she built an institution that shaped how an entire genre reached the world.

Patricia Chin is a cultural custodian, one of the unsung architects of Jamaica’s most successful export. She saw a revolution unfolding outside her shop window on North Parade and, rather than simply watching, found ways to amplify it across oceans.

The bridge she and Vincent built between Kingston and the world remains standing, carrying new generations of artists and sounds in both directions.

In an industry often dominated by extractive relationships—foreign labels strip-mining local talent for international profit—VP represents an alternative model: Caribbean-owned, family-operated, street-connected.

Miss Pat’s legacy isn’t just the records released or the artists championed. It’s proof that Caribbean people can control and benefit from their own cultural production.

The dancers on North Parade have long since dispersed. Gil Bailey’s voice no longer fills Saturday afternoons on New York radio. But the rhythms that moved them now pulse through speakers on every continent. Miss Pat made sure of that.

-30-