UNITED NATIONS | Millions of Illiterate Teens in Wealthy Nations says UNICEF

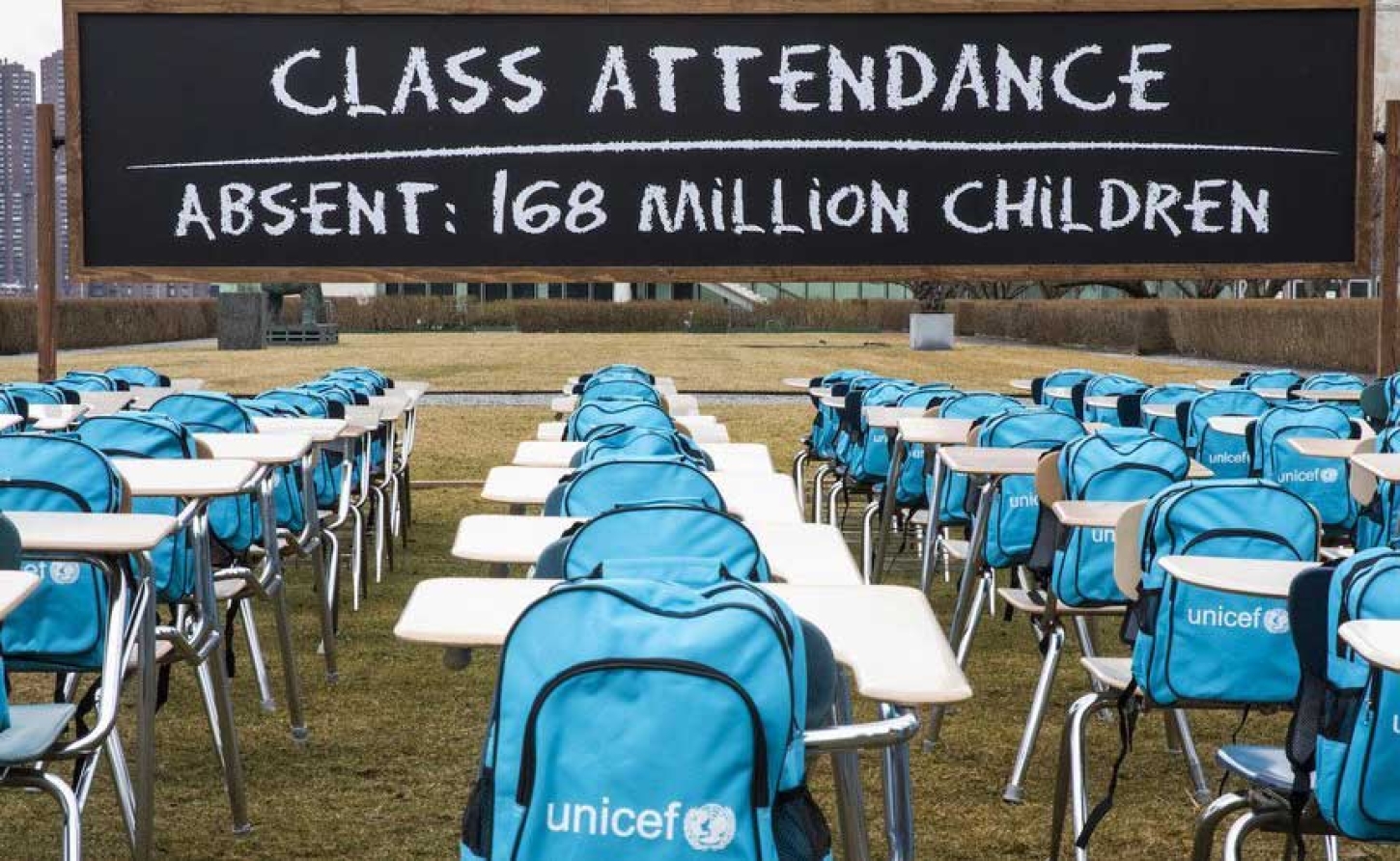

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica May 16, 2025 - In a damning indictment of educational failure across the developed world, UNICEF revealed Wednesday that approximately eight million teenagers in the world's wealthiest countries cannot read or understand basic texts—a shocking testament to pandemic-era policies that have left a generation academically crippled.

The UN agency's latest report paints a bleak picture: children across affluent nations are falling behind academically, struggling with deteriorating mental health, and battling rising obesity rates. These troubling trends suggest that even nations with abundant resources have fundamentally failed their youngest citizens.

"We're witnessing nothing short of a silent crisis," said Bo Viktor Nylund, Director of UNICEF's Innocenti research office, describing what he termed a "worrying benchmark for children's wellbeing" in countries that should, by all measures, be providing world-class support systems.

While the Netherlands and Denmark topped UNICEF's ranking of child wellbeing, followed by France, nations like Mexico, Türkiye, and Chile languished at the bottom of the list. This disparity raises uncomfortable questions about resource allocation and policy priorities even among nations with substantial wealth.

The academic fallout from COVID has been particularly severe. As schools shuttered and remote learning became the norm, students fell between seven and twelve months behind expected progress in core subjects. The pandemic didn't just interrupt education—it derailed it, with disadvantaged children bearing the heaviest burden of these setbacks.

Perhaps most alarming is the functional illiteracy crisis: across 43 studied countries, approximately half of 15-year-olds surveyed couldn't comprehend simple texts. This staggering statistic doesn't just represent academic failure—it forecasts diminished lifetime opportunities and economic potential for millions of teenagers.

The pandemic's mental health impact has been equally devastating. In nearly half of the countries with available data, children reported lower life satisfaction, while adolescent suicide rates—which had been declining—have plateaued. This psychological toll comes alongside physical health concerns, as obesity rates climbed among children aged five to 19, with those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds suffering disproportionately.

UNICEF's Nylund has called for a "coherent" and "holistic" approach that addresses "every stage" of childhood development. The agency specifically advocates for including youth voices in policy decisions—a recommendation that acknowledges how systematically children's perspectives have been overlooked during the pandemic response.

The report serves as a stark warning that even hard-won progress in child wellbeing remains "increasingly vulnerable" in wealthy nations. As these countries grapple with the pandemic's aftermath, UNICEF urges governments to focus interventions on disadvantaged communities to prevent further widening of already alarming equity gaps.

For millions of children across the world's richest nations, the pandemic didn't just interrupt their education—it may have permanently altered their life trajectories. The question now is whether governments will finally prioritize the recovery of a generation at risk of being left behind.

-30-