JAMAICA | Colonial Ghosts Haunting Justice: UWI Professor Takes Aim at Jamaica's Archaic Obeah Laws

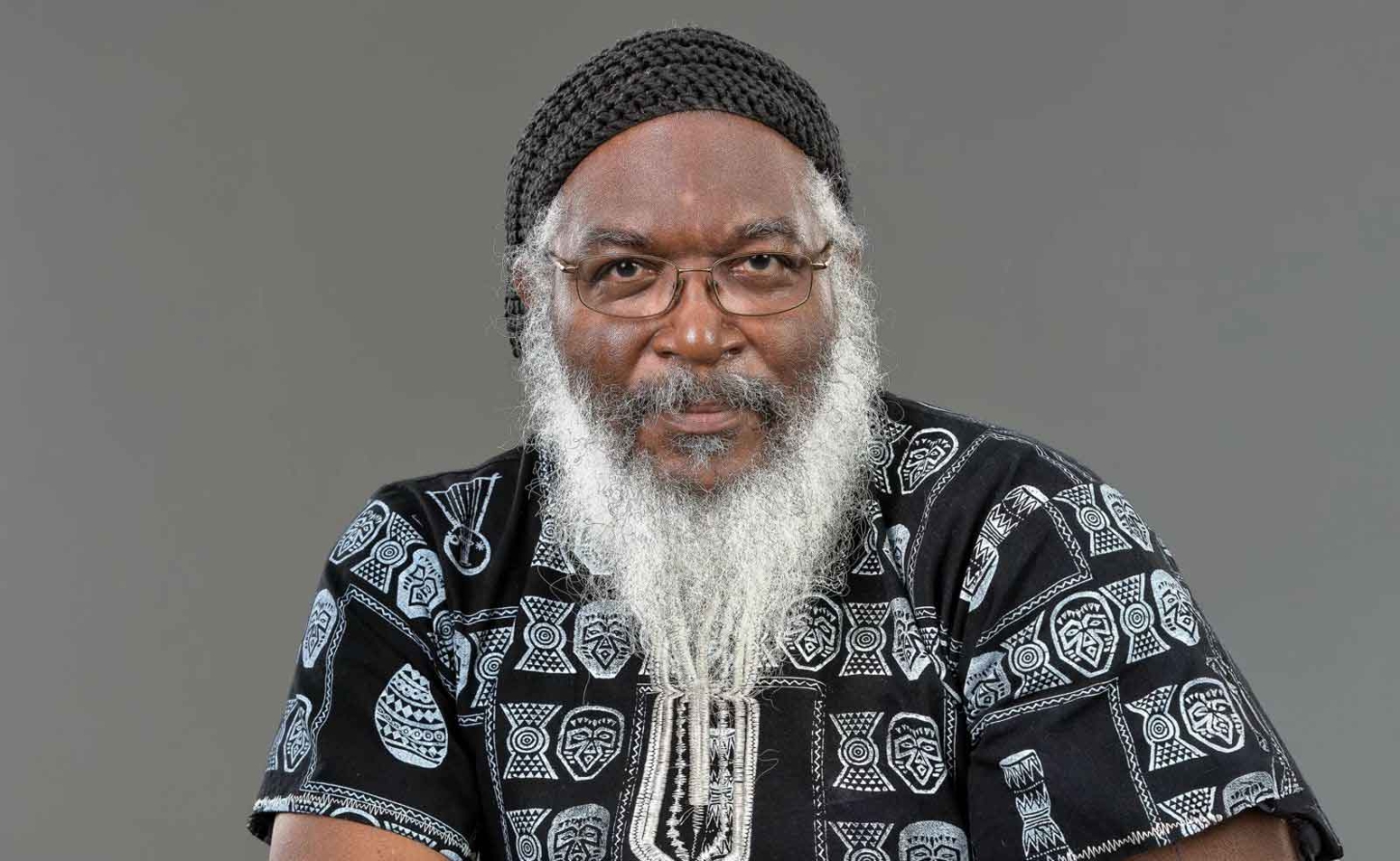

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, May 19, 2025 - In a bold challenge to Jamaica's colonial past, University of the West Indies Professor Clinton Hutton has launched a constitutional offensive against the 19th-century Obeah Act, a legal relic that continues to criminalize African spiritual practices more than 60 years after independence.

Filed in the Supreme Court last week Monday through prominent attorney and Pan-Africanist Bert Samuels, the challenge argues that multiple sections of the law violate fundamental constitutional rights, including freedom of religion, privacy, conscience, expression, and the right to seek and distribute information.

At the heart of Hutton's challenge lies a sworn declaration that what the colonial-era law defines as "obeah" actually represents retained African spiritual practices—a cultural heritage criminalized by slave owners fearful of rebellion and maintained by a post-emancipation system determined to suppress Black cultural expression.

The timing is no coincidence. Samuels confirmed that the legal action was catalyzed by the recent prosecution of Oshawn Grant in Montego Bay's St. James Parish Court, a case that has rekindled national debate about the archaic legislation.

Grant's conviction came after police raided his home, discovering what authorities deemed "obeah rituals"—burning incense in bedroom corners, a white T-shirt surrounded by money and candles, and labeled boxes reading "Money Rain," "Money House," and "African Powers." Reportedly wearing silver rings he feared removing, Grant allegedly told officers he was "fully guzu."

The Gleaner newspaper has taken an extraordinary step by publishing an editorial apologizing "on behalf of the Government and Jamaican state" to Grant for his conviction and J$5,000 fine. The publication specifically credited renowned lawyer and constitutional scholar Dr. Lloyd Barnett, whose expert analysis in a recent article highlighted the "absurdity and clear unconstitutionality" of Jamaica's continued enforcement of the Obeah Act, calling for its immediate repeal.

The editorial draws attention to the troubling historical context: obeah, practiced throughout the Caribbean, represents African spiritual traditions that slaves blended with Christianity and mysticism—practices colonial authorities feared might fuel rebellion or undermine slavery itself.

As Dr. Barnett noted in his analysis published in The Gleaner, the Obeah Act is ostensibly premised on targeting people who use it for fraudulent gain or to frighten others by pretending "to use any occult means" or claiming to "possess supernatural power or knowledge." He points out this vague definition could equally apply to many televangelists and Christian evangelists who profit from claims of healing powers and supernatural faith.

Perhaps most troubling is the Act's legal framework, which shifts the burden of proof onto the accused. Section 7 stipulates that anyone found with "any instrument of obeah" shall be presumed guilty "unless and until the contrary is proved"—a direct contradiction of the presumption of innocence enshrined in Jamaica's modern Charter of Rights.

This fundamental conflict was recognized as early as 1901, when Justice Charles Lumb called the legislation "an astounding piece of legislation" and "a danger and a menace to the liberty of the subject," noting its opposition to the principle that "a man is presumed innocent until his guilt is proved."

The historical roots of anti-obeah legislation reveal its deeply racist foundations. Laws from the 16th and 17th centuries were maintained by white slave owners anxious to suppress any supernatural belief systems among enslaved Black people. These laws explicitly characterized slaves as a "heathenish, brutish, dangerous kinde of People," and their resistance to slavery was often attributed to belief in supernatural powers.

Even after emancipation, Jamaica's white minority-controlled legislature maintained and strengthened obeah laws to preserve their dominance—moving in the opposite direction of England, where similar activities were being reduced to minor offenses.

As this constitutional challenge moves forward, it represents more than a legal technicality—it confronts Jamaica with fundamental questions about colonial legacies, cultural dignity, and whether a nation predominantly populated by people of African descent should continue criminalizing its own spiritual heritage in the 21st century.

-30-