HAITI"S Hidden Power Brokers: An Investigation into Economic Elite Influence

Introduction

As gang violence spirals across Port-au-Prince and Haiti teeters on the brink of collapse, international media coverage typically focuses on armed groups, failed governance, and humanitarian crisis.

But according to Caribbean analyst Jean Saint-Vil, writing under the pen name Jafrikayiti, this narrative obscures a crucial dynamic: the role of a small, economically powerful class of families who allegedly operate behind the scenes of Haiti's recurring political upheavals.

These families control 90% of Haiti's wealth and give a veneer that Haiti is a Black-run country when in fact they control virtually every business and entity in Haiti, argues Saint-Vil in his analysis.

The families—known collectively by the acronym "BAMBAM" (Brandt, Acra, Madsen, Bigio, Apaid, and Mevs)—represent what he characterizes as Haiti's "invisible elephants," wielding influence disproportionate to their small numbers.

In the 1980s, Haiti's upper class constituted as little as 2 percent of the total population, but it controlled about 44 percent of the national income, according to academic research on the country's social structure.

Today, an estimated 80 percent of Haitians live in absolute poverty, while this economic elite allegedly maintains extensive international business networks and political connections.

The allegations surrounding these families touch on some of the most serious accusations in contemporary Caribbean politics: orchestrating coups, facilitating drug trafficking, and funding armed groups.

But untangling fact from allegation in Haiti's complex political landscape requires careful examination of available evidence, legal proceedings, and competing narratives about who truly controls the impoverished nation.

The Economic Elite: Historical Roots and Modern Power

Several academic sources confirm the historical concentration of economic power among a small elite. During the Duvalier era from the 1950s-1980s, presidential decrees created monopolies for well-connected families in numerous industries: "mineral and petroleum exploration and exploitation, the construction and operation of television stations, the planting and processing of kenaf, sesame, and ramie, the processing of guano, the manufacture of chocolate, a fertilizer industry, the development of casinos and hotels, the construction of a sugar factory, the improvement of the telephone system," according to academic research published by Cambridge University Press.

By 1985, some 19 families held almost exclusive rights to import many of the most commonly consumed products in Haiti. The Mevs family, for instance, owns Haiti's largest industrial park, which warehouses 93 percent of the nation's imported food, according to Associated Press reporting.

These economic dynasties survived multiple political transitions, with Cambridge research noting that while some families "ultimately fell out with Duvalier," several key families "were the country's principal exporters before, during, and after both Duvaliers."

The wealth disparity is stark: The Bigio family came to own a $30-million mansion on a private island in Miami known as Billionaire's Bunker, where neighbors include Jeff Bezos and Ivanka Trump, The Globe and Mail reported in 2025. Meanwhile, most Haitians work for no more than US$2 a day in the formal economy, with the majority surviving in the informal sector.

Critics argue these families have used their economic leverage to influence political outcomes. Saint-Vil alleges they routinely pick "Black faces" to front governments that serve their interests, a charge that echoes in academic analysis.

According to Cambridge research on elite networks in Haiti, wealthy families offered "as much as $5,000 apiece to soldiers and police officers for their participation" in the 1991 coup against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, with one businessman quoted as saying "everyone who is anyone is against Aristide … except the people."

Allegations of Political Manipulation and Criminal Activity

The Manzanares Case: Haiti's Largest Drug Bust

In April 2015, Haitian National Police and the DEA conducted what became Haiti's largest drug bust in history. Officers seized between 700-800 kilos of cocaine and 300 kilos of heroin with an estimated U.S. street value of $100 million from a ship called the Manzanares, according to multiple sources including Coreys Digs and The Haitian Times.

The ship was carrying sugar imported by NABATCO, a company owned by Marc-Antoine Acra of the prominent Acra family. The vessel had docked at Terminal Varreux, owned by the Mevs family. Despite the massive seizure, only a low-ranking longshoreman was ultimately arrested and extradited, according to investigative reporting.

Judge Berge O. Surpris of the Port-au-Prince court indicted Marc-Antoine Acra for drug trafficking in July 2016. However, according to Haitian media reports, then-President Michel Martelly issued a decree making Acra a "Haitian Ambassador of Goodwill" to the Dominican Republic just six days before leaving office.

The DEA's handling of the case drew criticism from a U.S. Special Counsel, according to the Office of Special Counsel website, which lists an investigation into "DEA Investigation Fails to Hold Officials Accountable for Lax Security at Haitian Seaport, Illegal Drug Flow."

A 2024 investigation by Drop Site News revealed additional details, citing DEA whistleblower allegations that local station chiefs thwarted proper investigation of the case. The report noted that after the bust, "the Acra and Mevs families categorically denied any involvement in the drug seizure" and that "a local judge did issue an indictment against members of both families that was quickly dropped."

Gang Financing Allegations

Saint-Vil's analysis includes explosive claims about elite families allegedly funding armed groups. He cites the published confession of former gang leader Arnel Joseph, who allegedly described recruitment by oligarch families before his death in 2021.

However, the relationship between gangs and elites appears complex. A senior government official told InSight Crime that before President Jovenel Moïse's 2021 assassination, "50% percent of the G9's funding came from government money, 30% percent from kidnappings, and 20% percent from extortion."

Some business leaders have become victims of gang violence. Harold Marzouka Jr. told The Globe and Mail that his father was kidnapped, forcing him to pay a large ransom, and that construction on a trauma hospital he was trying to build was frozen after gangs demanded payment.

Historical Pattern of Foreign Interventions

Saint-Vil argues that foreign military interventions have historically served elite interests. During 19th-century upheavals, he notes, "multiple ransoms collected at gunpoint from the Haitian treasury by the Germans, the Brits, Americans, the Spaniards as well as the French went directly to compensate local white merchants who claim that the Haitian state failed to protect their affairs."

The 2004-2017 UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSTAH) also drew controversy. Former Brazilian Foreign Minister Celso Amorim told Brazilian media in 2022 that foreign pressure pushed for more aggressive tactics: "If you look at what the UN was saying at the time, primarily the US and some countries in Europe, it was that they all wanted us to use more force."

International Connections and Responses

The alleged influence of Haiti's economic elite extends beyond national borders through business partnerships, diplomatic connections, and international real estate holdings. Many families hold dual citizenship and maintain extensive overseas assets, particularly in the United States and Canada.

Several families have established businesses in North America. The Jaar family, who once held Haiti's Coca-Cola bottling monopoly, founded Montreal's Les Brasseurs RJ brewery in 1998, according to The Globe and Mail. During the 1990s U.S. embargo following the 1991 coup, some wealthy Haitians were able to profit from providing supplies to the same government that had sanctioned them.

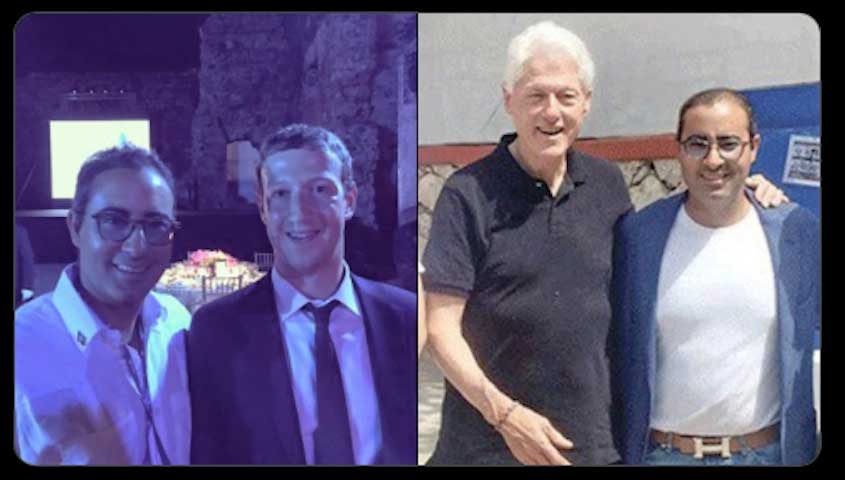

André Apaid Jr . - also from a BAMBAM family, is perhaps the most infamous white warlord in Haiti. Like others in the group of BAMBAM, Apaid Jr. was born in the U.S. His father, André Apaid Sr. was reportedly close to US-backed dictator Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier. Both men were allegedly key leaders of the 1991 and 2004 military coups against President Aristide.

The United States has also taken action, with the State Department announcing it would "pull visas of Haitian officials involved with criminal organizations." However, critics argue that international responses have been insufficient given the scope of alleged activities.

A 2019 report by Drop Site News revealed that a U.S. embassy cable noted: "although his embassy 'cannot confirm whether the alleged cabal of political insiders allied with South American narco-traffickers is controlling the gangs, we have seen indications of alliances between drug dealers, criminal gangs and political forces.'"

The so-called "Core Group" of international partners—including ambassadors from the U.S., Canada, France, Brazil, Spain, and Germany, along with representatives from the EU, UN, and OAS—has been criticized by Haitian activists for supporting what they view as illegitimate governments that serve elite interests.

Counter-Perspectives and Alternative Explanations

Not all analysts accept the thesis that economic elites are primarily responsible for Haiti's crisis. Some point to structural factors including centuries of foreign exploitation, natural disasters, and weak institutions as more fundamental causes.

Business community representatives, when they have responded publicly, typically deny allegations of criminal activity or political manipulation. After the Manzanares seizure, NABATCO issued a statement emphasizing its "excellent professional relationships" with Colombian sugar exporters and noting that the company "does not own vessels carrying cargoes of sugar."

Some economic historians argue that while wealth concentration is real, Haiti's problems stem from deeper historical factors. The country paid massive indemnities to France for over a century after independence, crippling its development. The 2010 earthquake caused estimated damages of $7.8 billion, devastating infrastructure and institutions.

International development experts note that Haiti's aid dependency has created perverse incentives, with some arguing that foreign assistance has inadvertently strengthened existing power structures rather than promoting inclusive development.

Security analysts also point out that gang violence has multiple causes beyond alleged elite funding, including the proliferation of weapons from abroad, breakdown of state institutions, and economic desperation among urban youth.

Current Implications and Path Forward

As Haiti faces unprecedented gang control over approximately 80% of Port-au-Prince, according to UN estimates, the debate over elite influence has practical implications for potential solutions.

Saint-Vil argues that any lasting solution must address what he sees as the root cause: "People of good will in the United States, Canada, Europe – worldwide – must listen to the Haitian People's loud and persistent demand that Black Nationhood and Black humanity be finally shown due consideration and respect."

Current proposals for international intervention, including a UN-authorized, Kenya-led multinational force, face skepticism from some Haitians who view foreign military presence as historically serving elite interests rather than popular welfare.

Gang leader Jimmy Chérizier has positioned himself as fighting against the elite system, telling ABC News: "The first step is to overthrow Ariel Henry and then we will start the real fight against the current system, the system of corrupt oligarchs and corrupt traditional politicians."

However, the complex relationships between various actors—gangs, political figures, business elites, and international partners—make simple solutions elusive. As Haiti expert Robert Fatton told The Washington Post, any path forward may require "an armistice or 'informal pact'" acknowledging the power that various factions now wield.

The allegations raised by Saint-Vil and other critics highlight fundamental questions about Haiti's governance: Can meaningful democracy emerge while such extreme wealth concentration persists? How can international partners support genuine reform rather than existing power structures? And most urgently, how can ordinary Haitians escape the cycle of violence and poverty that has trapped the country for decades?

While definitive answers remain elusive, the growing international attention to elite influence in Haiti's crisis suggests that any sustainable solution must grapple with the country's deep-seated inequalities—economic, political, and social—that have persisted since independence over two centuries ago.

This investigation is based on original analysis by Jafrikayiti (Jean Saint-Vil), supplemented by additional research into publicly available sources, court documents, and international reporting. The allegations presented reflect claims made by various sources and should be understood as part of ongoing debates about Haiti's crisis rather than established facts.

-30-