CARIBBEAN |Starving Cuba: Trump's Oil Blockade and the Caribbean's Deafening Silence

As Washington tightens its economic noose around Havana, the region that should be shouting loudest remains conspicuously quiet

By WiredJa Staff | February 15, 2026

The crisis arrived faster than anyone anticipated. Canadian airlines suspended all flights to Cuba this week, unable to refuel their aircraft on an island strangled by fuel shortages. Russian carriers followed within hours.

Across Havana, three-quarters of a million Canadian tourists who normally flood the island annually have nowhere to land, and those already there scramble for repatriation flights. The collapse is no longer theoretical—it's unfolding in real time, measured in days and weeks rather than months.

This is the result of Donald Trump's executive order threatening tariffs on any nation supplying oil to Cuba, a blockade so effective that even Mexico—Cuba's largest oil supplier and supposedly an independent actor—has ceased shipments despite President Claudia Sheinbaum's warnings of humanitarian catastrophe.

According to reporting by The Guardian's Ruaridh Nicoll, the speed of Cuba's deterioration has caught diplomats off guard, with one ambassador noting that extreme suffering in cities is now "a matter of weeks" away.

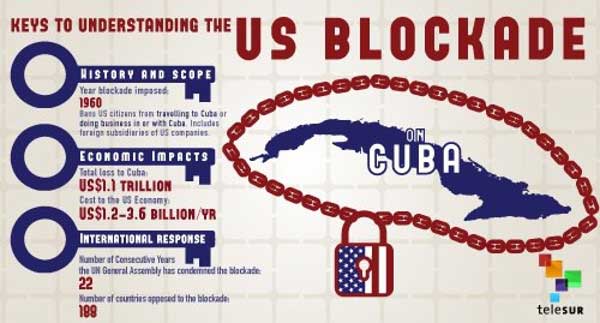

The Mechanics of Economic Strangulation

What distinguishes Trump's approach from previous US pressure campaigns is its brutal efficiency.

What distinguishes Trump's approach from previous US pressure campaigns is its brutal efficiency.

By threatening secondary sanctions on oil suppliers, Washington has effectively deputized the global economy to enforce American foreign policy objectives.

China and Russia expressed outrage but ultimately acquiesced. Mexico sent 800 tons of aid as consolation for cutting off the oil that keeps Cuban society functioning.

The message is clear: cross the United States on Cuba, pay the economic price.

The human cost materializes in grimly mundane ways. Universities have closed, sending students like 22-year-old nuclear physics student Adrian Rodriguez Suárez scrambling home to provinces where electricity is even more scarce than in Havana.

Weddings scheduled for March face cancellation. A motorcycle taxi driver advertises free rides for chemotherapy and dialysis patients to Havana's Calixto Hospital.

An enterprising craftsman in La Lisa sells cast aluminum cooking burners for $8 so families can cook over wood when the gas runs out.

"My mother is going crazy with this cooking on charcoal," one woman told Nicoll, before requesting anonymity to joke darkly about bequeathing the charcoal stove to her daughter as her only inheritance.

Meanwhile, US Chargé d'Affaires Mike Hammer toured eastern Cuba distributing American aid—a calculated performance of beneficence while his government's policies create the deprivation requiring relief. At a diplomatic reception in late January, Hammer reportedly told guests that Cubans have complained about "the blockade" for years, but now "there is going to be a real blockade."

The Quiet Retreat

The pressure extends beyond oil tankers and tariff threats. Jamaica has denied recent reports that it turned away a Cuban ship seeking LPG, just as it has denied reports of quietly reducing Cuban medical personnel by refusing to renew contracts. Yet the very existence of these reports—and the public backlash they've generated—reveals the climate of fear Washington's economic warfare creates.

Jamaicans, who have benefited from decades of Cuban medical support, aren't happy about the possibility of their government quietly capitulating to US pressure while maintaining official denials.

The pattern suggests that Trump's strategy works on multiple levels: the explicit threat of tariffs on oil suppliers, and the implicit understanding that any cooperation with Cuba—from accepting LPG shipments to renewing medical personnel contracts—could draw American ire.

This is how economic blockades function in practice: not just through dramatic cutoffs, but through the slow strangulation of normal relations as even friendly nations calculate whether standing with Cuba is worth the potential cost.

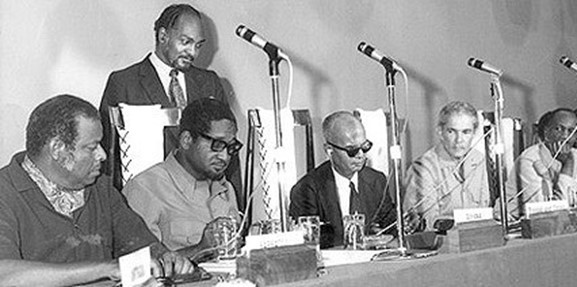

The Ghost of December 8, 1972

On that day, Prime Ministers Errol Barrow of Barbados, Forbes Burnham of Guyana, Michael Manley of Jamaica, and Eric Williams of Trinidad and Tobago announced the simultaneous establishment of diplomatic ties with Cuba, breaking the US-led isolation of the island.

These were not regional superpowers or nations secure in their independence. Barbados had been independent for just six years. Trinidad and Tobago for a decade. These were small, vulnerable nations with enormous economic exposure to American pressure.

Yet they chose sovereignty over submission. Their decision paved the way for other Caribbean nations to build strong relations with Cuba despite US disapproval, establishing a principle that the region would determine its own relationships rather than accept Washington's veto over Caribbean diplomacy.

That moment represented Caribbean courage at its finest—newly independent nations asserting that formal independence meant actual independence, that sovereignty wasn't merely a ceremonial status but a practical commitment to making decisions based on regional interests rather than imperial diktat.

Now, fifty-four years later, the Caribbean faces a test of whether that legacy means anything at all.

Where is CARICOM's Voice?

Here's what should concern every Caribbean nation: if Washington can economically strangle a sovereign state of 11 million people with impunity, what prevents similar treatment of smaller islands that displease American strategic interests?

Here's what should concern every Caribbean nation: if Washington can economically strangle a sovereign state of 11 million people with impunity, what prevents similar treatment of smaller islands that displease American strategic interests?

CARICOM has a regularly scheduled intersessional meeting in Basseterre, St. Kitts on February 24, where Cuba will likely appear on the agenda as it routinely does given the longstanding CARICOM-Cuba relationship. But this is not a routine moment.

Diplomats are warning that extreme urban suffering is "weeks" away. The World Food Programme is planning for catastrophic humanitarian crisis. Airlines have grounded operations. Universities have closed.

Yet there has been no emergency CARICOM session. No urgent convening of heads of government. The region appears content to wait for a scheduled meeting to address what amounts to economic warfare against a Caribbean neighbor.

The question isn't whether Cuba will be discussed on February 24—it's whether CARICOM will treat this crisis with the urgency it demands. Will the region produce concrete solidarity measures, or merely issue another statement expressing concern while Washington's blockade tightens?

Will there be proposals for humanitarian corridors, collective fuel-sharing agreements, or coordinated diplomatic pressure? Or will CARICOM handle the deliberate starvation of 11 million people as just another agenda item?

The contrast with 1972 is devastating. Four newly independent nations showed more courage then than an entire regional bloc demonstrates now, despite CARICOM having far greater institutional strength, economic resources, and international legitimacy.

Barrow, Burnham, Manley, and Williams risked everything to assert Caribbean sovereignty. Their successors can't even call an emergency meeting.

This acquiescence sets a dangerous precedent. It signals that Caribbean nations will tolerate extra-territorial enforcement of US foreign policy objectives, that economic coercion trumps international law, and that Washington's designation of a government as illegitimate justifies any measure to remove it—regardless of humanitarian cost.

It suggests that the brave decision of December 8, 1972 was merely a historical anomaly rather than a defining principle of Caribbean independence.

The World Food Programme, already struggling to deliver Hurricane Melissa relief due to fuel shortages, now plans for a far larger crisis. Empty tourist haunts in central Havana host war correspondents on breaks from Ukraine, positioning themselves to cover the fall of one of the world's last communist states. The diplomatic quarter prepares evacuation scenarios.

And the Caribbean? It waits for February 24, seemingly oblivious that precedents established in Havana today may determine what's permissible in Kingston, Port of Spain, or Bridgetown tomorrow—and that the legacy of Barrow, Burnham, Manley, and Williams hangs in the balance.

This article draws on reporting by Ruaridh Nicoll for The Guardian, "No fuel, no tourists, no cash – this was the week the Cuban crisis got real," published February 15, 2026.

-30-