CARIBBEAN | One From Ten Leaves Nought: The Federation Dream That Still Haunts the Caribbean

By Calvin G. Brown

On January 3, 1958, Princess Margaret stood before the newly inaugurated Federal Parliament in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, christening what many believed would become the "United States of the Caribbean."

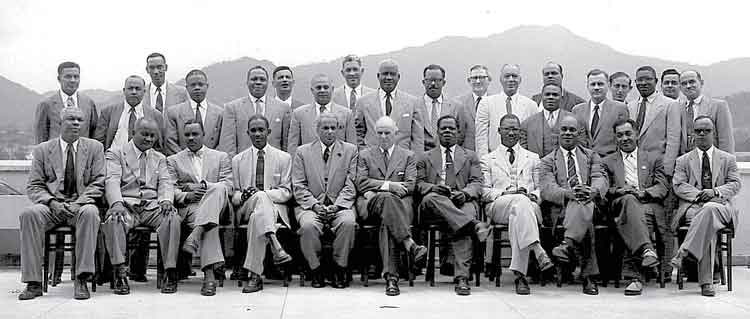

The chamber was electric with possibility—ten British colonies spanning from Jamaica in the west to Trinidad in the south had finally coalesced into the West Indies Federation, a political union designed to shepherd the region from colonial dependency to collective independence.

It was the culmination of decades of pan-Caribbean dreaming, a moment when the scattered islands of the British West Indies glimpsed their future as a single, powerful nation.

At the heart of this vision stood the West Indies Federal Labour Party, established in 1956 under the leadership of Jamaica's Norman Manley.

United by socialist principles and a shared determination to break free from colonial rule, the WIFLP advocated for rapid independence, stronger economic ties with Britain, the United States, and Canada, and most critically, the creation of a federal government powerful enough to transform fragmented colonies into a viable nation-state.

When federal elections were held in March 1958, the WIFLP won decisively, capturing 26 of the 45 seats in the Federal Parliament. Victory seemed to validate the federalist dream.

Yet the opposition West Indies Democratic Labour Party, led locally by Jamaica's Alexander Bustamante and his Jamaica Labour Party, had won 17 seats—and Bustamante had no intention of accepting defeat quietly.

The cousin and bitter political rival of Norman Manley, Bustamante represented rural interests and championed individual island autonomy over federal union.

From the Federation's first breath, he would prove to be the Jamaican fly in the ointment, relentlessly campaigning against what he characterized as a drain on Jamaican resources and sovereignty.

Even in this moment of WIFLP triumph, the seeds of destruction were already sprouting.

The Fatal Contradictions

The most glaring weakness was financial: the federal government was prohibited from levying income taxes for its first five years, leaving it dependent on per capita contributions from member territories.

Its maximum annual revenue—a paltry £1.9 million sterling—was smaller than the budget of the Port of Spain city council. This was not a government; it was a beggar among islands.

Worse still, the political arithmetic was perverse. Jamaica, with over 1.6 million residents and contributing the lion's share of federal revenues, found itself underrepresented in the Federal Parliament.

Trinidad and Tobago, the federation's economic powerhouse thanks to its oil wealth, faced similar marginalization while the smaller Eastern Caribbean territories wielded disproportionate influence.

The arrangement bred resentment from the start: why should Jamaica and Trinidad subsidize smaller islands while being outvoted by them?

Then there was the question of freedom of movement. The federation's constitution promised that citizens could move freely between territories—a noble principle that Trinidad feared would trigger mass migration to its oil-rich shores without corresponding federal mechanisms to manage the economic consequences.

Jamaica shared similar anxieties. Each island wanted the benefits of union without surrendering the power to protect its own interests.

And hovering over everything was the Chaguaramas controversy. The United States had leased the Chaguaramas peninsula in Trinidad for a naval base in 1941, and there was tremendous political pressure to reclaim it as the site of the Federal Government.

Eric Williams, Trinidad's leader, supported the recovery of Chaguaramas but was wary of alienating the Americans. The issue became a symbol of the Federation's impotence—unable even to assert control over its intended capital.

But perhaps the most fatal flaw was one of leadership and commitment. Neither Norman Manley nor Eric Williams—the two most prominent figures in British West Indian politics—stood for election to the Federal Parliament.

They remained in control of their island power bases, free to criticize the Federation from the sidelines while pursuing their territories' particular interests. Their absence signaled to the region that the Federation was not worth their full commitment. If the architects of federation would not serve it, why should anyone else believe in it?

The Federal Maple one of two ships donated by the Government of Canada to the West Indies Fereration effort.Jamaica's Departure and Williams' Mathematical Verdict

The Federal Maple one of two ships donated by the Government of Canada to the West Indies Fereration effort.Jamaica's Departure and Williams' Mathematical Verdict

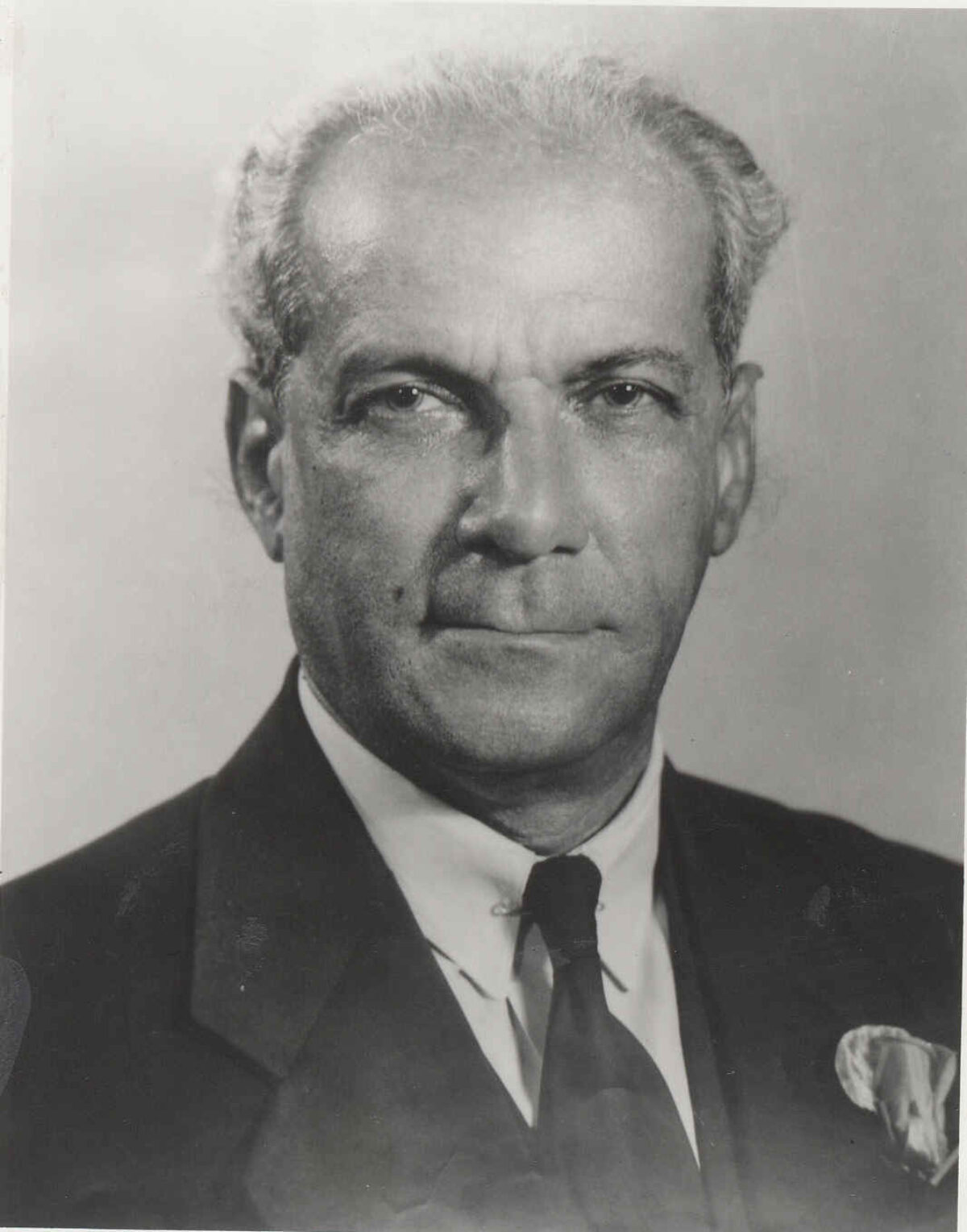

Alexander Bustamante's campaign was brutally simple and devastatingly effective: "Federation No." Two words that encapsulated every Jamaican anxiety about subsidizing smaller islands, surrendering sovereignty to a weak central government, and tying the island's economic future to territories that seemed more burden than benefit.

Bustamante hammered relentlessly on the mathematics of inequality—Jamaica paying the most while having the least say—and painted the Federation as Norman Manley's vanity project that would impoverish ordinary Jamaicans.

By 1960, the political pressure had become unbearable. Britain had privately intimated to Manley that Jamaica was eligible for independence on its own, destroying the foundational argument that federation was the only path to freedom from colonial rule.

If Jamaica could achieve independence alone, why share it with nine other territories? Manley, caught between his federalist principles and Bustamante's populist onslaught, made a fateful decision: he would let the Jamaican people decide via referendum.

On September 19, 1961, Jamaicans went to the polls to answer a single question about their continued participation in the Federation.

The result was decisive: 54% voted to withdraw. Manley had gambled and lost. He would spend the following months arranging Jamaica's orderly exit and negotiating the terms of separate independence, but his dream of a West Indian nation was finished.

In Trinidad, Eric Williams watched the Jamaican referendum results with grim calculation. Without Jamaica—the Federation's largest territory, its biggest economy, its most populous member—what remained?

Trinidad and Tobago would now be responsible for approximately 75% of the federal budget while holding less than half the seats in the Federal government. The mathematics were untenable, the political situation absurd.

On January 15, 1962, Williams delivered his verdict in a speech that would echo through Caribbean history: "One from ten leaves nought." The phrase was mathematical derision wrapped in resignation—subtract Jamaica from the ten-member federation and you are left with nothing.

It was both an explanation and a justification for Trinidad and Tobago's withdrawal. By May 31, 1962, the West Indies Federation was formally dissolved. The dream had lasted four years and five months.

The Haunting Legacy

"One from ten leaves nought" did not die with the Federation. The phrase has become Caribbean political shorthand for the futility of regional unity, invoked whenever integration efforts falter, whenever sovereignty trumps solidarity, whenever island interests override regional vision.

It is the ghost at every CARICOM summit, the whisper behind every failed Caribbean cooperation initiative, the mathematical proof that seems to doom every attempt at building what the Federation promised.

The Federation's collapse in 1962 did not kill the dream—it merely forced it to evolve. In 1968, the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA) emerged from the wreckage, followed by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in 1973, signed at Chaguaramas—the very site of the naval base controversy that had symbolized the Federation's impotence.

These institutions represented more modest ambitions: economic cooperation rather than political union, coordinated development rather than shared sovereignty. The lesson had been learned.

The region would integrate cautiously, incrementally, always preserving the escape hatch of national autonomy.

Yet even these diminished dreams have struggled against the Bustamante legacy. In Jamaica, the political DNA of "Federation No" continues to pulse through successive Jamaica Labour Party administrations—a strand of insularity and xenophobia that treats regional cooperation with suspicion and Caribbean solidarity as a threat rather than an opportunity.

While the People's National Party, heir to Norman Manley's federalist vision, remains openly supportive of CARICOM and Caribbean integration, the JLP instinctively defaults to the arithmetic Bustamante mastered: what does Jamaica gain, what does Jamaica lose, what does Jamaica owe to anyone else?

This tension plays out across the region. When Trinidad and Tobago recently broke ranks with CARICOM over the "Zone of Peace" declaration—welcoming U.S. military operations while fourteen other member states reaffirmed their commitment to non-militarization—observers heard echoes of Eric Williams' 1962 calculation.

One editorial titled "One from 15 leaves nought" warned that Trinidad's actions resurrect "a dangerously dissonant spirit: the idea that Trinidad and Tobago, insulated by mineral assets, economic power, and geopolitical leverage, can afford to disrespect its neighbours when it suits its strategic interests."

The irony is bitter. The very institutions that survived the Federation's collapse—the University of the West Indies, the West Indies Cricket team, the Caribbean Court of Justice—stand as testament to what Caribbean unity can achieve when nations commit to shared purpose.

Yet these successes coexist with a persistent failure of political will, a refusal to subordinate national interests to regional imperatives, a lingering belief that "one from ten leaves nought" is not just historical observation but mathematical law.

Perhaps the deepest tragedy is the "what if" that haunts every discussion of the Federation. What if British Guiana and British Honduras had joined, providing the larger markets that might have made federation economically irresistible to Jamaica?

What if Manley and Williams had stood for federal parliament, lending their prestige and political skill to building a functioning central government? What if Britain had made independence truly contingent on federation, forcing the territories to make it work?

Instead, the Caribbean got Bustamante's arithmetic: ten minus one equals nothing. And sixty-three years later, the region is still trying to prove that equation wrong—still struggling to build solidarity from sovereignty, still haunted by the ghost of a federation that promised everything and delivered only the enduring lesson that in Caribbean politics, division comes naturally and unity requires a faith the region has yet to sustain.

-30-